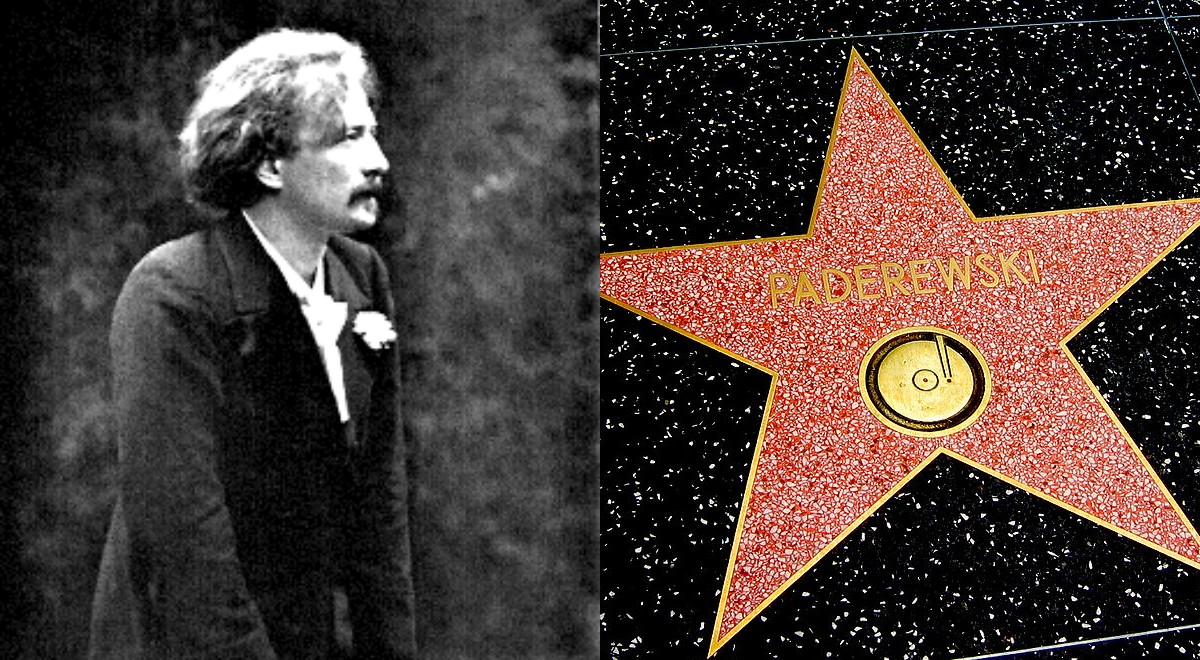

Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941)

Paderewski is one of the most extraordinary figures in Polish history. He was a world-famous pianist and composer, politician, diplomat, statesman, celebrity, friend of several American presidents and a great Polish patriot. He was widely known as a philanthropist, a man with a big heart and mind. Paderewski had a special influence on the history of his homeland, the history of music and the history of culture on a global scale.

1860 - 1878 Paderewski was born on November 6, in the village of Kuryłówka, in the Podolia Province of southeastern Poland (now Ukraine), into the family of an estate administrator. A few months later his mother died. Ignacy and his sister Antonina showed great musical talent. In 1878 Paderewski received diploma from the Music Conservatory in Warsaw and became a piano teacher at his alma mater. Besides his pedagogical work, Paderewski devoted time to composing and perfecting his pianistic technique.

1888 Paderewski made a sensational debut at the Salle Erard in Paris. Young Pole became a star with invitations pouring in from all over Europe: Brussels, Antwerp, Budapest, Prague, St. Petersburg, London, Paris, Berlin, Poland, Switzerland, and Romania. Young pianist became friends with a Spanish violinist Pablo Sarasate and the French composer Camille Saint-Saëns. The Dutch painter Laurence Alma-Tadema left us a painterly image of the pianist.

1889-1913 Paderewski's career was gaining momentum, with recitals in France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, including the cities of Paris, Nantes, Utrecht, Hague, Arnhem, Berlin, London. Paderewski was the second Polish pianist after Chopin to give concerts at the homes of London’s aristocracy. He was asked to play private concerts in front of Queen Victoria at the Windsor Castle. Later Paderewski recalled: "She addressed me in the most beautiful French and really made me feel like a real king.” Paderewski performed at St. James’s Hall, a program of Chopin pieces that was met with one of the wildest scenes of enthusiasm ever seen in London. Newspapers reported an extraordinary public demonstration and a pianist who was literally attacked by the crowd. It turned out that before Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Michael Jackson there was Ignacy Paderewski and “Paddy-mania”. How did a musician from a backwater in Eastern Europe become the first global pop star? When did this modern Paderewski cult come about? Like Beatles-mania decades later, it took place in England, very likely in 1890, but the real “Paddy-mania” broke out in America in the years that followed.

1889-1913 Paderewski's career was gaining momentum, with recitals in France, Belgium, Germany, Switzerland, Romania, Poland, including the cities of Paris, Nantes, Utrecht, Hague, Arnhem, Berlin, London. Paderewski was the second Polish pianist after Chopin to give concerts at the homes of London’s aristocracy. He was asked to play private concerts in front of Queen Victoria at the Windsor Castle. Later Paderewski recalled: "She addressed me in the most beautiful French and really made me feel like a real king.” Paderewski performed at St. James’s Hall, a program of Chopin pieces that was met with one of the wildest scenes of enthusiasm ever seen in London. Newspapers reported an extraordinary public demonstration and a pianist who was literally attacked by the crowd. It turned out that before Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Michael Jackson there was Ignacy Paderewski and “Paddy-mania”. How did a musician from a backwater in Eastern Europe become the first global pop star? When did this modern Paderewski cult come about? Like Beatles-mania decades later, it took place in England, very likely in 1890, but the real “Paddy-mania” broke out in America in the years that followed.

On November 17, Paderewski made his American debut at the New Music Hall, now Carnegie Hall, which had opened six months earlier. The hall had 2,700 seats and 1,000 standing places. The orchestra was conducted by Walter Damrosch. Paderewski became friends with Damrosch, and their friendship lasted many years. During the first performance the pianist was very nervous, which was noticed by critics. One of them reported that a "picturesque young man, very slim, very nervous and embarrassed, with a pale face, crowned with a mane of brownish-reddish hair entered the stage” After the next concert press wrote about the Polish artist as the greatest contemporary pianist, equal to Rubinstein. Meanwhile, Paderewski himself didn’t know about it, instead of reading the newspapers, he was preparing for next performances. In the meantime, it turned out that he couldn’t practice in the hotel because it was full of elderly residents, so he had to practice in a cold, unheated, gloomy Steinway piano warehouse on 14th street. He practiced there until the morning with two candles burning to prepare for the 10 a.m. rehearsal. When Paderewski went on stage for the third concert, he was literally falling from exhaustion, only a sudden surge of adrenaline allowed him to forget about exhaustion, despite sore fingers he once again delighted the audience and demanding critics.

After three concerts, he had to play recitals in the then small hall of Madison Square Garden, but the number of people willing to come was so large, that Paderewski's performances were moved to Carnegie Hall, where all the places, both seated and standing were sold out. Following one of the concerts, the audience, mostly women, burst onto stage, preventing Paderewski from leaving the venue. After the concerts in New York, it was time for Boston Music Hall, where a Polish pianist performed with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, considered the best in the country.

1892 On New Year's Eve and New Year's Day, Paderewski performed at the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago, where he set another record. This time, he played to an audience of 4,000, who again went wild for him. Paderewski later performed in St. Louis, Buffalo, and Philadelphia. On January 23, Paderewski returned to New York to perform at a packed Carnegie Hall, and then at a packed Madison Square Garden. On February 3, he performed at the Luther Place Memorial Church in Washington, D.C., to rave reviews, and then played in New Haven, Detroit, St. Louis, Buffalo, Philadelphia, and back in New York. When Paderewski returned to New York, the police had to close off entire streets in the areas where he was scheduled to appear. Crowds stormed the ticket booths, the police would cordon off his hotel day and night, something that had never been seen before in America. It seems Paderewski was experiencing some of the inconveniences of a rockstar life some 50 years before the term “rockstar” existed, but Paderewski certainly was not playing rock’n’roll. Paderewski became an extremely popular artist in the United States. At the end of the first tour Paderewski, wanting to repay the American audience for their warm welcome, proposed ending the tour with a performance, the profits of which were to be donated to the Fund for the construction of Washington's Arc in New York. March 28, a concert that had an exceptional setting: the hall was decorated with US and Polish flags. The artist, together with the Boston Symphony Orchestra, played Schuman's “Concerto in A minor” and his own “Concerto in A minor”, then performed Liszt's Hungarian Rhapsody.

On April 29, Paderewski's first concert tour in America ended. That day, seen off by hundreds of people, the artist boarded a ship in New York harbor. The tour brought in over $100,000, which was a huge amount for those times. Paderewski became the highest-paid pianist in America. Newspapers jokingly wrote that when Mr. Paderewski started taking such amounts to Europe, the American treasury would soon run out of gold to cover his fees. The Polish pianist stayed in the States for one hundred and thirty days, during which time he performed one hundred and seven times, traveled over 19,000 miles (30,400 kilometers) by train. He was listened by over 200,000 people. However, on the tour between concerts, the artist had no access to his instrument, and practiced on a quiet keyboard the whole time. He complained about his spine and struggled with a painful hand injury. During a March 16 concert at the Lyceum Theatre in Rochester, New York, Paderewski strained muscles and injured a finger on his right hand. Such a serious injury should have prompted the artist to rest; doctors warned of permanent disability, but Paderewski insisted on honoring the terms of his contract, even though it meant learning to play only four fingers of his right hand. He never regained full use of the finger. After returning from America, Paderewski was constantly on tour, giving several concerts a week. His last performance in Europe that year took place at the home of the American-English financial tycoon William Waldorf Astor.

The second concert tour in 1892 was much better organized. The organizers provided him with a comfortable railway lounge. A special Pullman car attached to regular trains had a bedroom, a library, an elegant dining room and a lounge with a piano for practice. In the adjacent car there was an additional piano with a tuner, space for the American impresario, treasurer, servants, accountant, personal secretary, photographer, two porters Augustus and Charles and a personal chef, James Cooper. Another car was intended for journalists and reviewers reporting on the concerts in the media, as well as for Paderewski's friends and guests. After reaching the destination, the car was detached from the train and directed to a siding. Crowds of fans gathered at stations and along the train routes. Dramatic scenes took place in front of the concert ticket offices, people waited many hours for tickets to be sold, they came early in the morning for evening concerts. This was something America had never experienced before. Everywhere, the audience greeted Paderewski with applause, he was received in the salons of American politicians and the cream of society. Paderewski could now practice freely and relax in his living room, but bad luck continued to haunt him, he neglected the wound on his finger and had to undergo surgery. That same day, he played with four fingers and with a dressing on one finger. Of course, the concert ended with bloody stains on the keyboard. After each concert tour, Paderewski returned to New York, where he stayed at the Windsor Hotel. At the Hotel, he was considered a good billiards player, a billiards enthusiast. One day, at the billiard table, he met the future president of the USA, William McKinley. When it came to outfits, Paderewski would spend a fortune on silk shirts, waistcoats, tailcoats, patent leather shoes and loafers that were custom made in London, fur coats, Lock’s hats, luxury watches, cufflinks, tiepins, or cigarette boxes.’

1893 Third tour, Paderewski established contacts with Poles who came to America with hopes for a better tomorrow. The fame that Paderewski enjoyed among Americans allowed Poles to raise their heads, now they could feel proud of their origins. Paderewski became not only an American idol, but also a spiritual leader of the enslaved Polish nation. Concerts in New Haven, Boston, Carnegie Hall, Portland, Music Hall Buffalo, Hartford, Brooklyn Rochester, Music Hall, Cleveland, Madison Square Garden, Washington DC, Auditorium Theatre, Chicago, Paderewski travelled in his own saloon car all the time, which of course contributed to the creation of the legendary aura around the master. A witness's account: “The great master rehearsed wonderful compositions in this car all day long. Yesterday, the admiring car cleaners could listen to him for free, without giving up their day's work, as long as they were busy with work. This explains why the two cars standing on either side of the pianist's saloon car were cleaned so many times"

1895-1896 A massive tour from Maine to the Pacific. Paderewski arrived in California after having already given 49 concerts in three months on a route of almost ten thousand kilometers. He was already a superstar, an idol to all ladies and a subject of envy to every man in America. It is impossible to guess what Paderewski knew about California when he arrived in San Diego. What a stunning experience it must have been for the Great Pianist when he had to walk nearly a mile from a little railroad station to the Fisher Opera House along a dirt road, passing on his way only one dilapidated structure, housing a dubious little gambling house! Many years later, in his Memoirs he would say that in 1896 San Diego was “hardly a village”. But The Fisher Opera House turned out to be one of the best and most modern concert halls in California whose 1,400 seats were filled that night by a genuinely elegant and musically inclined audience. Most of the concert listeners were the guests of the brand new, fashionable, and luxurious Hotel del Coronado, the ticket price was out of reach for the majority of the town’s population. Paderewski's first concert tour in California lasted only 25 days, he visited six cities, giving a total of 14 concerts. It was a huge program that only a man of steel physical condition, phenomenal mental resilience and boundless love for what he did could muster.

While staying in California Paderewski meets Herbert Clark Hoover (1874–1964) the future President of the United States (1929-1933). A young student, had no money to pay his tuition at Stanford. Afraid of being expelled, he and his friend decided to organize a concert to raise money for his education. The star of the evening was the world-famous pianist and composer - Ignacy Jan Paderewski. The bad timing of the concert during Holy Week resulted in unsold tickets and a considerable financial loss. Even the artist’s honorarium could not be covered in full. When Paderewski learned about this, he not only waived his honorarium, but paid for renting the hall. His kindness was repaid by President Hoover over 20 years later, when he provided humanitarian relief to war-ravaged Poland via the American Relief Administration, thus saving hundreds of thousands of people from starvation. Paderewski continued on to give concerts at Carnegie Hall, New York, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Collingwood Opera House, Poughkeepsie NY, Steinway Hall, New York, Washington DC, New Haven, Hartford, Boston Music Hall, Armory Hall, Hartford, Portland, Pierce Hall at New England Conservatory, Boston, Buffalo, Carnegie Music Hall and The Music Hall, Baltimore. The New York Times announced the amounts that foreign artists take home after the season. Paderewski topped the list, along with Enrico Caruso.

1897-1999 For many years, Paderewski dreamed of finding a home to which he could return after long and exhausting tours. In 1897 he purchased in Poland Kąśna Dolna, estate about 60 miles southeast of Kraków. Two years later Paderewski married Helena von Rosen- Górska, the same year, he bought the Riond- Bosson big estate in Switzerland. The villa was surrounded by a vast park and garden, and from the huge terrace there was a view of Lake Geneva and the majestic Mont Blanc. The Riond- Bosson residence became a longed-for home, where he gathered a collection of outstanding works of art.

1900 From December 1899 to mid-May 1900, Paderewski toured the United States. Paderewski family was traveling in a private, well-equipped railway carriage. The artist performed at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia, the Academy of Music in Richmond, the Columbia Theatre in Washington, Carnegie Hall, Boston Music Hall, and the Academy of Music in Richmond, Virginia. Unlike many other great contemporary pianists, Paderewski was also a businessman. As his fame grew, his name started appearing on all kinds of merchandise: from soaps and creams with the words ‘We love Paddy’ written on them, to shampoos made according to the ‘Paderewski formula’, to Oat meals with his name, candies and Paddy-shaped lollipops, even Louis Vuitton suitcases. While Paderewski didn’t run any of the businesses, he certainly profited from them. Soon enough, he became a very rich man. Paderewski may have been a great businessman, a brilliant manager of his own image, and a master of self-promotion, he still had one more asset. This asset was Poland. In fact, throughout all this time Paderewski was running another – perhaps the biggest and most successful marketing campaign ever run by one person. He was indefatigable in raising support and money mainly for Polish charity causes. Paderewski was a one-man think tank, a foundation against defamation, a fund-raising institution, a Polish embassy abroad, and a living monument to and proof of the immaculate public image of Poland. Paderewski donated 10,000$ to establish The Paderewski Foundation for Young American Composers, and donated 50,000 French francs on leaving the country. In this time those sums were a fortune.

At the turn of the century, the artist was a very wealthy man, but he was able to generously share his wealth with countrymen, as well as with private individuals and foundations from all over the world. Over the years, he supported various causes: unemployed musicians in England, the United States and Switzerland. He established funds for playwrights and composers in Poland, supported the construction of the Concert Hall in Switzerland, the reconstruction of the Cathedral in Lausanne, the unemployed, war orphans, the construction of the Health Center and the Breast Center in Zakopane, Disease Sanatorium in the same city, orphanages and the Maternity Center in New York. Paderewski allocated large amounts of money to the construction of dormitories for music students in France, to the Allied Soldiers' Hospital, for Jewish refugees from Germany in Paris. He gave the largest individual contribution of $28,600 to the American Legion of Disabled Veterans. In Poland, he commissioned a monument to Woodrow Wilson, to symbolize Poland's gratitude for its newfound independence. Paderewski established a foundation for young American musicians and students at Stanford University, supported the Paris Conservatory, established a scholarship fund at the Ecole Normale in Paris, financed students at the Moscow Conservatory, sponsored many monuments, including the Debussy and Edouard Colonne monuments in Paris, the Liszt Monument in Weimar, the Beethoven Monument in Bonn, the Chopin Monument in Zelazowa Wola, the Kosciuszko Monument in Chicago, and the Washington Arch in New York.

Paderewski gave his first concert in this tour at Old City Hall in Portland, then he performed at Carnegie Hall. He later performed at Brooklyn Academy of Music, California Theatre, San Francisco, Los Angeles Theatre, Auditorium Odeon Theatre, St. Louis, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Hyperion Theatre, New Haven, Tulane Theatre, New Orleans, Central Presbyterian Church, Buffalo, Salt Lake Theatre, Convention Hall, Kansas City, Cincinnati Music Hall, Sioux City, Metropolitan Opera House, St. Paul, Auditorium Theatre, Chicago, Austin Opera House, Grays Armory, Cleveland, Old City Hall, Portland, Footguard Hall, Hartford, Tacoma Theatre, Baker Theatre, Rochester, Sherry's Ballroom, New York, Lyceum Theatre, Memphis, Newark Theatre, Sweeney & Coombs Opera House, Houston, Light Guard Armory, Detroit, Columbia Theatre, Washington DC.

1902 On February 14, took place the premiere of Paderewski's opera "Manru” which was a great celebration of Polish music on the stage of the Metropolitan Opera. Aleksander Bandrowski (1860-1913) performed the title role, and Marcelina Sembrich (1858-1935) played the role of Uliana. The orchestra was conducted by Paderewski's friend Walter Damrosch, who convinced Andrew Carnegie to build Carnegie Hall. Paderewski entered the stage eight times including three times with Damrosch. Never in its history had the Metropolitan Opera exploded with such a great explosion of applause, which greeted Paderewski and resounded from the orchestra to the highest balconies. The “New York Herald” listed the names of 110 of the most influential and wealthy people present at the premiere, along with information about the boxes they were in and in what company. Of the rich and famous, the press reported the presence of John Rockefeller Jr., Cornelius Vanderbilt and Colonel John Jacob Astor. The second ‘’Manru” performance took place on March 8, 1902, at the same time as Paderewski's recital at Carnegie Hall. The Herald Tribune claimed the next day, that three thousand listeners at Carnegie Hall and four thousand who filled the auditorium of the Metropolitan Opera paid homage to the genius of Ignacy Paderewski.

1904 - 1905 After concert tour in Australia and New Zealand, Paderewski played in San Francisco, San Jose, Los Angeles, Carnegie Music Hall, Jefferson, Court Square Theater, Springfield, National Theatre, Washington, Academy of Music, Philadelphia, Academy of Music, Norfolk, Woolsey Hall, New Haven, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Plymouth Congregational Church, Minneapolis Boyd's Theater and Opera House, Carnegie Hall, New York, Savannah Theatre in Savannah. During a tour near Syracuse, Paderewski suffered a serious accident. The artist's private train was derailed. He was forced to cancel all concerts; the effects of the strong shock were felt by him for many years to come.

1907-1909 During the tour, Paderewski performed at the White House at the invitation of President Theodore Delano Roosevelt and his wife. It turned out that the US President was perfectly aware of the situation in European countries. He also knew a lot about Poland, mainly due to his sympathy for the Polish novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz. Paderewski became friends with Sienkiewicz, and used to say that "art is an expression of the immortal part of man". During this period he gave innumerable concerts in Boston, New York, Baltimore, Washington DC, Philadelphia, Buffalo, New Haven, Pittsburgh, Hartford, Newark, Bridgeport, Memphis, Louisville, Spokane, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Seattle, Indianapolis, San Francisco, Santa Barbara, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, Pueblo, Albuquerque, Cleveland, Fort Worth, Cincinnati, Oklahoma City, Minneapolis, Los Angeles, Portland, Milwaukee, Little Rock, Oakland, Altoona, Nashville, Kansas City, Palo Alto, Salina, Richmond, Tacoma, Allentown, Binghamton, Washington, Baltimore, Newark, Minneapolis, Chicago, St. Louis, Lyric Theater, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Hartford, Bridgeport, New Haven City Convention Hall, Buffalo, Krueger Auditorium, Newark, Grand Opera House Wilmington, Auditorium Odeon Theatre, St. Louis, Orchestra Hall Chicago, Santa Barbara, Carnegie Music Hall, Pittsburgh, Memphis Lyric Theatre, Oklahoma City, Convention Hall Kansas City, Cincinnati Music Hall, Macauley’s Theatre Louisville, Richmond Coliseum Auditorium Theatre Chicago, Grays Armory Cleveland, Milwaukee.

1911 For years, Paderewski promoted Chopin in the USA throughout 3,000 concerts; in 1911 he wrote a book about Chopin, and later published his complete works. Paderewski made friends with many famous people in America, including Andrew Carnegie, philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr., who built Rockefeller Center in New York, financial tycoon William Waldorf Astor, the outstanding Bostonian Joshua Montgomery Sears, the railroad tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt, banker J.P. Morgan, William Chase and publisher and press tycoon Joseph Pulitzer.

1914 In mid-January Paderewski had to suspend his concerts for a while, his right hand was practically paralyzed. He went to San Francisco for treatment and then came to Paso Robles, where he stayed at the Paso Robles Inn. Paso Robles was a small town consisting of only two streets, a few hundred permanent residents and vast uninhabited areas. The attractions of Paso Robles were its natural, sulfur-rich, hot springs and mud baths, which were said to have extraordinary healing properties. Apparently, this was true, because after less than three weeks of bathing in bubbling mud, daily massages and drinking mineral water, Paderewski regained manual use of his right hand to a degree that allowed him to resume his interrupted tour of the United States. The wonderful climate and dazzling landscapes must have impressed Paderewski, he decided to invest in land in Paso Robles. On February 4th he bought a plot of land west of the city, to which five weeks later he added an adjoining acre. He named the property "Rancho San Ignacio." Over the next two years, he bought three more parcels, which he named "Rancho Santa Helena" in honor of his wife. Paderewski became one of the largest landowners on the Central Coast, planting plum orchards, walnut orchards, an almond plantation, and allocating 81 hectares to a vineyard. Ten years later, he planted Zinfandel vines. Paderewski's wines became one of the best wines between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Later wine made from Zinfandel grapes grown on Rancho San Ignacio received several prestigious awards, becoming an important factor in the recognition of the Paso Robles. Over the years Paderewski pumped more than three million of today’s dollars into his ranches. The memory of Paderewski survived in California and is still alive today. In the Paso Robles Inn, which was rebuilt after the fire, one of the banquet halls bears his name and many contemporary vineyards in Paso Robles bear his name. Paderewski was a good spirit of this land.

1915 -1916 During World War I, the political landscape of Europe was transformed, Paderewski used all of his influence and skills to advance the cause of Polish independence on the international stage. He arrived in the United States on April 17, 1915, this time not as a beloved virtuoso, but as a representative of the Polish Fund for the Relief of Victims, founded with Henryk Sienkiewicz in Vevey, Switzerland. On May 30, Paderewski gave a speech at a rally of the Polish community at the Tadeusz Kościuszko monument in Chicago. The patriotic demonstration in Humboldt Park gathered over 150,000 people. For the next years, taking advantage of his enormous popularity and authority, Paderewski traveled throughout the United States. He gave over 140 charity concerts and gave over 340 speeches in support of Poland. In Polish and English, he spoke about the history and traditions of Poland, about a democracy older than that of Western Europe, spoke about Polish literature, science and culture, and Poland's role in defending Christianity. At Polish rallies and meetings of American elites, Paderewski shared his vision of an independent Poland. As the political and war situation developed, eventually acting as a representative of the Polish National Committee and delegate of Roman Dmowski, he supported a program of specific actions, led by the armed participation of the American Polish community in the war against the Entente countries.

1916 Paderewski enjoyed enormous popularity; wherever he gave concerts he was greeted by crowds, invited by numerous organizations and city authorities, often met with New York City authorities. Paderewski met with Colonel Edward M. House, one of President Thomas Woodrow Wilson's closest friends and advisors, who encouraged the president to support the cause of Polish independence. House served as Wilson's chief negotiator in Europe during the peace negotiations (1917–19) and was Wilson's chief deputy at the Paris Peace Conference. Interestingly, Colonel House was not a soldier at all. This title was given to him because of the respect and importance in American diplomacy. Paderewski used the opportunity to try to interest the American authorities in Polish affairs. On February 22, one of the most important concerts in Paderewski's life took place in Washington. He played a concert at the White House and later had a long conversation with President Wilson about the fate of Poland. They speculated about the borders, studying various historical maps of Europe. On November 6, in New Jersey, Paderewski met again with President Wilson and discussed the Act of November 5, announced the day before, which created the Republic of Poland. The next day, President invited Paderewski to his home, where they had a long conversation, and at the end of it, Wilson said, "My dear Paderewski, I can tell you that Poland will be resurrected and will exist again." On November 27, in Chicago, Paderewski gave a speech dedicated to the memory of the recently deceased Henryk Sienkiewicz. In the following months, he gave speeches in which he asked for support for Polish victims of World War I, organized rallies in defense of Polish independence. He raised millions of dollars to help Poland, working with U.S. President Wilson and Herbert Hoover. Charlie Chaplin wrote, "During World War I, I met Paderewski at the Ritz Hotel in New York and greeted him enthusiastically, asking if he was at the hotel to give a concert. With papal gravity, he replied, “I do not give concerts when I am serving my country. On October 6, 1916, recruitment for the Polish Army began in all Polish community centers throughout America. Young boys were encouraged by Paderewski’s fervent appeal “to join the ranks, to arms, to fight.” Women- mothers, wives, and girlfriends—followed the recruitment campaign, organizing themselves into circles of women who helped the Polish Army. Such circles operated at Polish parishes and organizations.

1917 January 11 New York: Paderewski sent the American President an open letter about Poland and the need to restore the country's independence. A memorandum was an important contribution to the final shape of Point 13th of the President's appeal to the Senate, concerning the Polish question and the restoration of Polish independence. In April Paderewski gave a lot of public speeches to Poles in the USA, becoming the informal leader of Poland. He appealed for financial aid to be given to his compatriots, and for political pressure to create a Polish Army, paving the way for official recognition of Poland's independence. New York May 23, Paderewski sent out an open letter to the American authorities about the need to create a Polish Army to fight alongside the Allied Forces. Later Paderewski sent a letter to President Wilson in which he appealed for official recognition of the Polish National Committee, which was created on 15 August in Lausanne, with Roman Dmowski as its president and Paderewski as its representative in the USA. He wrote an appeal to Poles in America asking to help Poles in their country. At the Kosciuszko monument in Chicago, he delivered another patriotic speech, which turned into a great patriotic manifestation with the participation of over 100,000 people. Paderewski said: “The cause of the nation is not a business from which one should withdraw when instead of profits it brings losses. The cause of the nation is a continuous matter, constant work, unwavering perseverance, uninterrupted sacrifice from generation to generation”

From the beginning of his operations in America, Paderewski began to work on the project of creating a Polish army in the USA, which if transferred to Europe, would be a serious bargaining chip for Poland's efforts to regain independence. Since the United States was not yet formally participating in the war while maintaining its neutrality, the formation of army, or training of volunteers, could not take place on their territory. On the other hand, Canada, neighboring the United States as the dominion of Great Britain, was a party to the war. At a convention of Polish Falcons in Pittsburgh, Paderewski called for the formation of Polish Army which would fight alongside Americans in World War I. In Paris, Paderewski became a member of the newly formed Polish National Committee and was delegated to be its representative in the United States. Soon the French government dispatched a Polish-French mission to America to recruit volunteers to the Polish Army from among the two and a half million Polish immigrants in the United States. Because the United States continued to be neutral, the training camp for Polish Army volunteers was established by the British Dominion of Canada, at Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario. Paderewski visited the camp and addressed the troops. The second military camp for Polish volunteers was established in St. Johns, Quebec. These were formally camps of the Canadian Army, but Polish volunteers from the USA, and in much smaller numbers also from Canada, trained there.

A training camp named after Tadeusz Kościuszko was established in Niagara on the Lake. It was not only Poles who reported to the draft centers. There is a well-known story of a Sioux Indian who decided to put on a Polish uniform to fight shoulder to shoulder with Poles in the name of homage to Tadeusz Kościuszko, a hero of the American Revolutionary War.

On April 4, 1917 in Pittsburgh, publicly announcing the initiative to establish a Polish Army in the United States under the name "Kosciuszko's Army". Immediately afterwards, the U.S. entered the war. On October 6, the army was officially recognized by the United States as an autonomous unit and thus received formal permission to recruit in the USA. Since then, recruiting has gained additional momentum. In addition to the camp in Niagara-on-the Lake, Ontario, a new training camp was established in the US, at Fort Niagara, on the American side of the Niagara River. Thousands of new volunteers arrived there. In November, nearly 3,000 were stationed in the camp, designed for 500-600 soldiers. Winter was approaching and the climatic conditions were rather not conducive to living in tents. Organized legions of Polish women started sewing works to provide volunteers with warm clothes, sweaters, scarves, socks and gloves. After the Commission's long efforts, the American government made Fort Niagara available on the other side of the border for Polish needs. This temporarily resolved the housing problems and recruitment could continue. On November 4, 1917, the Polish flag was solemnly raised in the military camp in Niagara-on-the Lake. On November 21, Paderewski received a parade of soldiers from Kosciuszko's Army there and spoke to the army. On February 23, 1918, the political control over the Polish Army in France was established by the Polish National Committee. Paderewski visited army again in June 1918, received the parade and said: “I come to you with a word of love on my lips, with immeasurable gratitude in my heart. (...) Go ahead! Go with faith in the sanctity of our cause, go with faith in victory!" The Polish Army in France quickly grew with additional thousands, as the news of its existence spread throughout the fighting in Europe, and all over the world. Massive numbers of Polish deserters from German and Austrian troops started to arrive there. In the summer and fall of 1918, a total of over 60,000 people arrived in France, which made the Army a powerful force of around 80,000 (some sources estimate it at 100,000). They were mostly well-trained soldiers. Thanks to the efforts of Paderewski and Dmowski, the army was transported to Poland in 1919 in the spring of 1919. Volunteers from America took part in battles with Ukrainian and Bolshevik troops. In February 1920, they took over Pomerania from the Germans. Then they took part in the expedition to Kiev, defended Lviv from the Bolsheviks and fought on the outskirts of Warsaw in August 1920.

1918 On January 8, in a speech on the aims of war and conditions of peace (item 13), President Wilson recognized Polish independence as one of the conditions for future peace in Europe. At the turn of June and July, Paderewski began work on establishing the Polish White Cross, a civilian institution aimed at supporting the army. Helena Paderewska became the head of the organization. In America, Paderewski was considered the spiritual leader of the Poles, in his speeches he raised the issue of the fight for an independent, united Poland, and also collected funds for the Fund for Aid to Victims of War in Poland. On September 13, Paderewski and Dmowski appealed to President Wilson to recognize Poland's right to the Eastern Borderlands, as well as to Silesia, Greater Poland and Pomerania (including Gdańsk). After World War I, Paderewski donated $28,600, the largest single donation to aid American war veterans. Meanwhile, Americans loved him not only for his music, but also for his heart and charitable work.

1919 Ignacy Jan Paderewski became the Prime Minister of the Polish government and Poland's representative to the League of Nations. He signed the Versailles Treaty, which restores Polish sovereignty after more than 120 years. Paderewski’s life's dream came true: Poland once again took its place on the map of Europe. There was something thrilling, unusual, symbolic, and even mystical about a great artist representing the resurrected Poland at the World Peace Conference. Everyone knew that, as an artist, he stood at the top. But something else dominated the political struggle that was raging at the Conference all the time: his unique, assertive personality, in which his iron will and delicate sensibility were inseparably intertwined; his historical knowledge with the speaker's creative inspiration; the gift of establishing personal contact, being open to the interlocutor and looking for common ground with him, combined with the ability to keep one's own opinion. All this was based on refined culture, and impeccable manners and supported by knowledge of languages, history, geography, and economic issues. Paderewski maintained respect and communicated with them at the level of universal values, the general good, and common justice towards the representatives of great powers and small nations. He often collided with a different value system of the other side, with ruthlessness and political cynicism, with the interests of the stronger imposed by force on the weaker. But he persevered. During the Peace Conference Paderewski made efforts to transport his army to Poland. Despite the obstacles thrown at his feet by Germany and England, under the command of General Haller, the army was transferred to the now independent Poland and its soldiers, becoming an essential force in the war with Russia in 1920. After the recently ended World War I, Poland was badly devastated. The Polish nation was starting to starve. Over a million people were fighting for survival. Paderewski appeals to the United States government for help. Herbert Hoover, head of the recently established American Relief Administration, came to help. He did not hesitate for long. He was particularly concerned about the fate of Polish children. Thanks to Hoover's support, thousands of tons of food, cotton, clothing and means of transport flowed to Poland. This was a huge support for the Polish nation. For some reason, President Hoover became involved in helping Poland, often making decisions against the resistance of other Allied countries in Europe. As the representative of Poland, Paderewski signed the Versailles Treaty, which restored Polish sovereignty after more than 120 years. When Hoover was in Paris in 1919, Paderewski approached him to thank him for his charitable work for Poland. Hoover replied: "You probably don't remember me, but I am one of the two students, then 18 years old, whose debt you forgave. I am also very grateful to you for your help." The friendship between the Polish artist and the President of the United States lasted until Ignacy Paderewski's death. Hoover was always interested in the Polish cause. He was perfectly aware of the repression and persecution of the Polish nation. He noticed Polish problems like no other. For his services, he was repeatedly distinguished by the Polish government. In 1922, he received honorary citizenship of Poland, and there is a Hoover square in Warsaw.

1921 Paderewski resigned from all political posts and moved permanently to Paso Robles, California. His welcome on March 26 was truly royal. The train stopped at the small building of the Paso Robles train station. The crowd that came to greet the Paderewski’s was so large that getting off the train was almost impossible. Maestro Paderewski also proved to be an artist in the field of winemaking. Paderewski focused on the certain grape varieties and his Zinfandel later conquered California. Paderewski consulted with prof. Frederic T. Bioletti at the University of California on the soils and the varietals of grapevines to plant on 200 acres at Rancho San Ignacio. Later he planted 35,000 Zinfandel cuttings purchased from the Borden Nursery in Riverside, California and an acre of Muscat for his wife who loved these table grapes. The California Grape Grower published an article on August 1, 1922, stating that a crop of 12 ½ tons of Mission Grapes was harvested at Madame Paderewski’s Santa Helena Ranch that fall from 1 ½ acres of full bearing grapes. Paderewski’s Zinfandel grapes were later crushed and wine was made at the York Mountain Winery. Paderewski’s Zinfandel won gold medals at the California State Fair in 1934.

1922 Paderewski's financial difficulties forced him to begin performing again. On November 9 he resumed his concert tours throughout America and Canada. His first performance in years at Carnegie Hall in New York on November 22, 1922 was described as one of the greatest events in the history of 20th century music. A widely known and respected statesman appeared on stage. The hall honored him with a standing ovation. Then the great virtuoso gave a concert, playing with absolute perfection. The audience, the world of music, fellow artists, critics, impresarios were enchanted, delighted and carried away.

1923 Paderewski received the honorary Doctor of Law degree from the University of Southern California for his political achievements. Other Universities that honored Paderewski include Lvov, Yale, Jagiellonian, Oxford, Columbia, Glasgow, Cambridge, and New York University. Concerts in New York, Buffalo, New Haven, Pittsburgh, Detroit, San Francisco, Raleigh, Chicago and Ann Arbor. At the invitation of the American Legion and the Polish Army Veterans Association, General Haller came to America for the first time. At the invitation of the American Legion and the Polish Army Veterans Association, for the first time came to America Józef Haller (1873- 1960), Polish lieutenant general and legionary in the Polish Legions during the First World War.

1924 Concerts in Buffalo, Chicago, Youngstown, Birmingham, Memphis, Louisville, Pittsburgh, Detroit, San Francisco, Evansville, Akron, Hartford, Dallas, Fort Worth, Los Angeles, Portland, Milwaukee, Wilkes-Barre, Shreveport, Tucson, Tulsa, Nashville, St. Louis, Springfield, New York. Paderewski was also a famous composer. His piano miniatures were particularly popular. His Minuet in G major, op. 14 no. 1, written in the style of Mozart, became one of the most recognizable piano compositions of all time. All of his compositions evoked a romantic image of Poland. They contain references to Polish dances and highland music. Paderewski's love for his homeland was reflected in the titles of his compositions, including Polish Fantasy op. 19 and Symphony in B minor "Polonia" with a quote from Dąbrowski's Mazurka.

1928-1929 Concert tours in the USA; tour around Australia and New Zealand. In 1928, Paderewski gave concerts in America. He influenced the shape of the world he lived in. On the tenth anniversary of Poland regaining independence, Paderewski received letters of thanks from many famous people in the States, as well as from the governors of most American states. In 1928 on the tenth anniversary of Poland regaining its independence, Paderewski received letters of recognition from many famous people in the States and around the world as well as from the Governors of most American states. Paderewski influenced the shape of the world he lived in. It is hard to believe, but in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Polish virtuoso recorded 100 record albums in America alone! In the Fall of 1929 Paderewski canceled his American tour after an operation for appendicitis. In the presence of a notary from Morges in Switzerland Paderewski wrote his last will and testament; in this will he stated that, after proper provision to guarantee a lifetime income for his wife and sister was made, his money should go to the Jagiellonian University in Kraków, Poland. In 1930, Paderewski placed his will in a deposit box at the Morgan Bank in Paris, paid with the money from his account; the will was discovered in 1949. Paderewski continued with concerts in Omaha, New York, Baltimore, Durham, New Rochelle, Des Moines, Austin, Atlanta, Troy, Dallas, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Lansing, Milwaukee, Beaumont, Madison, Lancaster, Brooklyn, NY, Washington DC, Nashville, Kansas City, Wichita, Syracuse, NY Greenville, Charlottesville, St. Louis, East Orange, Mankato, Rochester, Philadelphia, New York. In 1928 on the tenth anniversary of Poland regaining its independence, Paderewski received letters of recognition from many famous people in the States and around the world as well as from the Governors of most American states. Paderewski influenced the shape of the world he lived in. It is hard to believe, but in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s, Polish virtuoso recorded 100 record albums in America alone!

1930-1932 Anniversary of the artist's birth and concert tour in America (1930) January-May 1931 further concerts in America. On February 8th 1932 at Madison Square Garden in New York Paderewski gave an extraordinary concert, attended by a record audience of 16,000 people. The profit of $37.000 went to unemployed American musicians.

1933 February-April performances in the USA. Paderewski was a bridge enthusiast. In his free time Paderewski also liked to visit casinos, especially the Casino in Monte Carlo, and he was also very fond of cinema. He always tried to enter the cinema during the screening of a film, because otherwise the audience always stood up and gave him an ovation. Before one of the screenings of his favorite move in New York a dozen or so of the most ardent admirers lifted Paderewski onto their shoulders and carried him out to his car with the greatest enthusiasm. This way Paderewski did not manage to see the film at all. Towards the end of his life Paderewski tried another role as a film actor in Lothar Mendes’s film “Moonlight Sonata”. The film was a great success and so was Paderewski. It seems being successful was something Paderewski was always good at.

1937-1938 In 1937 he began editing Chopin's Complete Works. In 1938, Paderewski performed a 40-minute radio recital, broadcast live around the world, and carried in North America by the NBC Network.

1939 Last concert tour in the United States, last visit in California. There was nothing unusual in the public outpouring of love and tears that occurred in 1939 when he performed his farewell concert for the audience of eight thousand at the Los Angeles Shrine Auditorium, and then for almost as large of a crowd of his enthusiastic admirers at the San Francisco Civic Exposition Auditorium. The imperfections of the old man did not mean anything; with the diminishing sound of the last chords of his piano, one of the listeners jumped on the podium to kiss the pianist’s hands in a spontaneous act of admiration and thankfulness. Paderewski was truly the good spirit of California; when he died in 1941, the Los Angeles Times reported, “The passing of the immortal hero, Ignacy Paderewski, has become a profound personal loss to many in Southern California.” On February 8 Paderewski's radio recital was broadcasted by Radio City. On February 28, 1939 Carnegie Hall concert brought 50 million Americans to their radios. May 21 in Rochester, New York, was Paderewski's last public performance. The fame that Paderewski enjoyed in the United States was evidenced by the fact that in 1939 he was able to repeat his success with Madison Square Garden. On May 26, an evening concert was about to take place in New York, for which more than 16,000 tickets were sold. However, the performance was canceled at the last minute, because just before it began, Paderewski suffered a mild heart attack. When the news of the heart attack was announced, moving scenes took place among the distraught audience, many of them crying and praying for Paderewski's life. About 16,000 people who came to the sold-out concert went away disappointed. On May 31, Paderewski's address to the Polish community in America was printed in almost all Polish community newspapers. September 1, Paderewski treated a wartime defeat and the partition of Poland in 1939 as a personal tragedy. He witnessed the collapse of a country whose independence had been his driving force for much of his life. Following the outbreak of World War II, Paderewski conducted anti-Nazi campaigns from his home in Switzerland. The German Nazis placed Paderewski's name in the so-called Black Book, containing a list of "enemies of the Third Reich." Paderewski renewed his political and patriotic activities. He organized aid for war victims in Poland, sent open letters to politicians, and addressed the citizens of America, Great Britain, and France (as well as his compatriots in the USA and Poland) via radio recital in Radio City Music Hall. Paderewski served his fatherland until the last days of his life. His extraordinary nobility was not for show and was not an empty gesture. He was always loyal to his friends and opponents. He was also a hardworking and conscientious man.

1940 In September 1940, after his last journey across the Atlantic at the personal invitation of the US President, evacuated via France, Spain, and Portugal, Paderewski arrived in America on November 6, 1940. He stayed, as usual, at the Gotham Hotel at 5th Avenue and 55th Street; it no longer exists, but a few weeks later he moved to the cheaper Hotel Buckingham at 6th Avenue and 57th Street. He was short of money. Paderewski broadcast in French, English, and Polish, gave speeches at political meetings, and published articles in the press. Paderewski continued broadcasting speeches on the radio and made further efforts to appeal to Americans, as well as to Polish-Americans. His last concert, broadcast live by NBC, was listened to by 50 million people. To honor his 80th birthday concerts were organized throughout the United States. Revenue from these concerts went to the Paderewski Testimonial Fund, to purchase food and clothing and to support many charitable actions helping the victims of war.

1941 The “Paderewski Days" were held in America to celebrate the golden anniversary of his American debut. About six thousand concerts were organized in honor of the artist, the profits of which were allocated to aid for Poland. Despite his advanced age (80), Paderewski was still politically active. He gave speeches, supporting the spirit of his compatriots. He appealed to the world for help for Poland. The New York Times devoted two pages to the celebration of the 50th anniversary of his first concert in the United States. Paderewski appealed for help for Poland, spoke at rallies and meetings Day after day Paderewski was clearly losing his strength. His sister Antonina and friends advised him against going to Oak Ridge, New Jersey, where on June 22 he was to meet with the "Blue Veterans". June of that year was very hot. The unfriendly city, enveloped in heat and humidity, was sapping the old man's last energy. Meanwhile, the day before, the Germans had attacked the Soviet Union. Throughout the night, Paderewski, accompanied by his secretary and the Polish consul in New York, listened to radio announcements. The next day, Sunday, June 22, 1941, he went to Oak Ridge New Jersey, where he gave a long, fiery speech at a SWAP convention. The heat and emotions accompanying the meeting in the clearing in Oak Ridge, and the cold drink drunk to cool down, caused disastrous consequences. Pneumonia developed. The unequal fight lasted a week. Ignacy Jan Paderewski died in the country he loved with reciprocated love, in his hotel room at the Buckingham Hotel in New York. at 11:00 a.m. on Sunday, June 29, 1941. Just before his death, Paderewski verbally conveyed to his sister, Antonina who accompanied his brother until the last moments of his life, his will to be buried in a free Poland and to leave his heart in America. A Requiem mass at St. Patrick's Cathedral was celebrated by the Archbishop of New York, Francis Spellman. Paderewski's coffin was covered with the Polish flag and was resting on a carriage pulled by eight horses. According to reports, thirty-five thousand people stood outside the Cathedral. On 5 July, Washington DC Paderewski's funeral was accompanied with all military honors at Arlington National Cemetery thanks to a special Act by President Delano Roosevelt, approved by the Senate and the House of Representatives. But in fact, Paderewski wasn't buried after his funeral. According to the cemetery's documents, because Paderewski had not served in the armed forces of the U.S. or its allies, he wasn't eligible to be buried below ground. Instead, he was interred in the vault of the U.S.S. Maine Mast Memorial in the cemetery's Section 24. The Times article about his funeral noted that the plan was for his body to remain at Arlington only temporarily, "until such time as it can be sent to a free Poland for burial." But "such time" would turn out to be more than a half of a century. In 1986 Paderewski's heart was moved to the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa in Doylestown, Pennsylvania where it rests to this day.

1960 took place a celebration of the 100th anniversary of the birth of Ignacy Paderewski in the USA. He was one of the first heroes of popular culture. The celebration committee consisted of 138 personalities. President Eisenhauer delivered a message to the nation reminding the merits of Paderewski. Solemn masses were held, celebrated by the highest officials of the church. This 1960 Champion of Liberty issue stamp honored Paderewski, Polish musician and politician. The stamp depicted a medallion with Paderewski’s portrait.

1963 May 9, Arlington Cemetery, American President John F. Kennedy unveiled a plaque at Arlington Cemetery stating that the remains of the Polish statesman and musician were resting at the site temporarily. In May 1963, President John F. Kennedy, accompanied by an honor guard of 180 U.S. soldiers in dress uniforms, tried to remedy the injustice by dedicating a plaque honoring Paderewski at Arlington. In his remarks, Kennedy said that "that day has not yet come" when the body could be returned to a free Poland, "but I believe that in this land of the free, Paderewski rests easily." It took the fall of communism in eastern Europe to get Paderewski a ticket home.

1981 General Edward Równy, Lieutenant General of the United States Army of Polish descent, who was President Regan’s chief arms control negotiator with the Soviets, convinced President Reagan to commemorate the 40th anniversary of Paderewski’s death with a ceremony at Arlington Cemetery. In his speech President Reagan presciently stated that the Berlin Wall would be torn down and that when that happened, Paderewski would be re-buried in Poland. General Równy followed through on those promises.

1992 Since Paderewski wanted his ashes to rest in free Poland, on June 29th with President Bush aboard Air Force One, Paderewski's remains were officially transferred to Polish President Lech Wałęsa at a ceremony at Royal Castle in Warsaw, Poland. Ignacy Jan Paderewski now rests in peace in the crypt of St. John's Cathedral. His heart is encased in a bronze sculpture in the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa near Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Today a magnificent bronze plaque hangs next to the entrance to the Buckingham Hotel on the west side of Manhattan at 6th Avenue and 57th Street, informing us that this place was the last residence of Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941), prime minister of the Polish government, a great pianist, composer, and friend of six American presidents, whose patriotic efforts resulted in Poland regaining independence at the end of World War I. Paderewski made his debut at Carnegie Hall during his first tour of the United States in 1891 – we read on the plaque – and until his death he participated in a significant way in the cultural life of New York. Paderewski was an enthusiast of America, a country full of dynamism and momentum, accustomed to hard and honest work, opening up perspectives unknown to Europe at that time. Figures such as Ignacy Paderewski made a valuable contribution to American culture, and their efforts gained universal recognition. Paderewski was a double hero: of art and of the homeland. As an artist, he was able to delight and captivate the largest audiences with his art and the power of his talent. Thanks to this, he was able to pave his way into the world of politics and, as a result, do a lot of good for the homeland that he loved, respected and served above all else. When he undertook the mission of being a politician, wanting to work for peace and for Poland to regain its independence, the greats of this world said of him with full respect for this statesman that no country could wish for a better defender. In an appeal to the Polish Americans, he wrote: "The thought of a great and strong, free and independent Poland was and is the content of my existence, its realization was and is the only goal of my life" Ignacy Paderewski deserves to be remembered not only by his countrymen, but by every person for whom love of country and loyalty to a great cause are the noblest traits of human character.